Articles

~

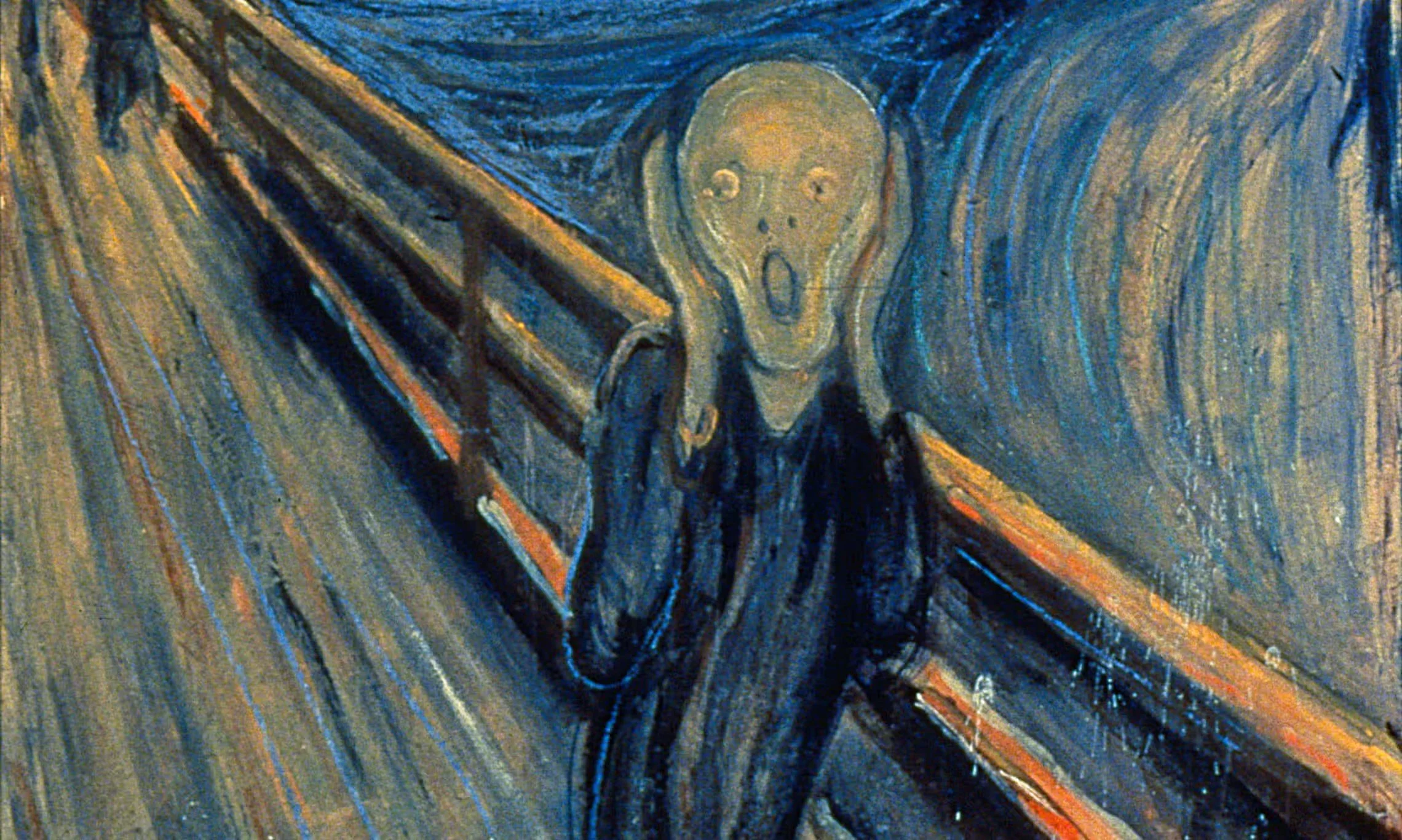

Abstract: Frantz Fanon’s relationship to the politics of recognition is ambiguous; securing recognition from one’s fellow members of a political community is necessary for the full realization of dignified freedom, and yet seeking such recognition can be equally damaging to this very freedom. This article seeks to clarify the ways that Fanon attempts to navigate this tension—what I call the “recognition trap”—and pave a middle path between the theorists of the recognition paradigm and its radical critics. Focusing on the ways that cultural considerations figure into Fanon’s later clinical writings and practices, this article argues that the Fanonian alternative to the recognition paradigm is a view of freedom as self-constitution, for which certain forms of recognition serve a necessary albeit subordinate function.

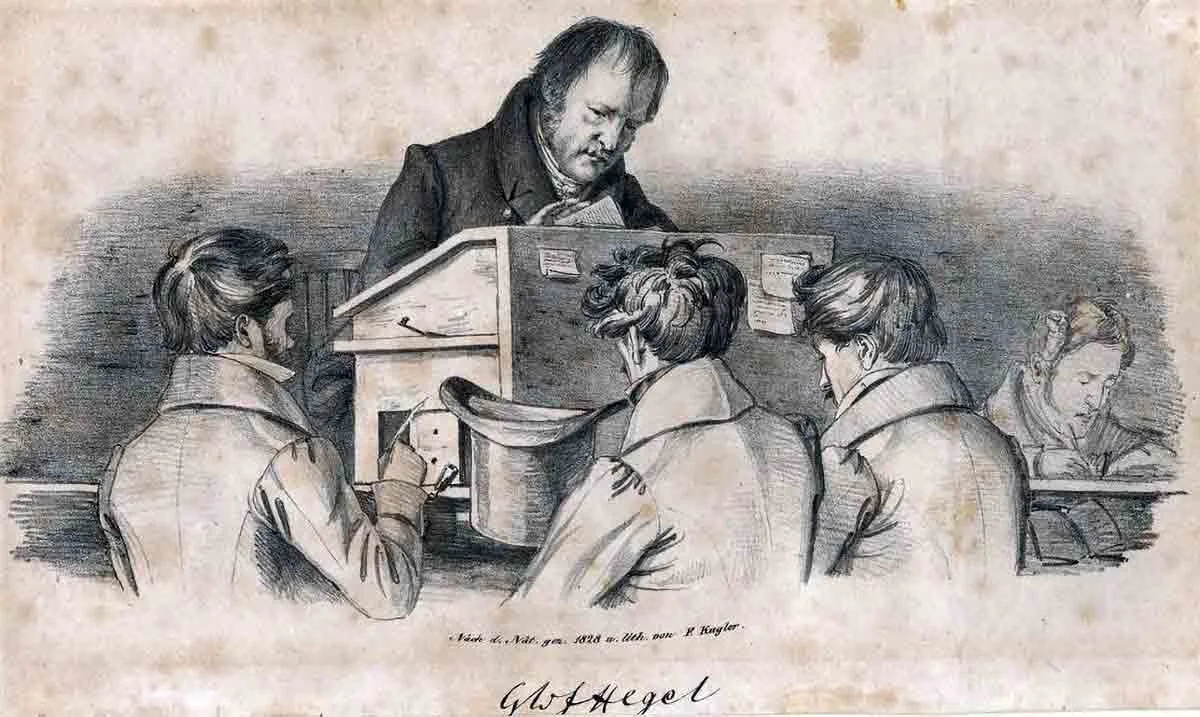

Abstract: In Hegel’s Philosophy of Right a gap exists between his promise of freedom and his description of the family. Hegel’s promise is to show the family as an integral aspect of a choice-worthy and free life, yet his description of this familial life appears to disqualify it as a sphere of freedom. By focusing on, rather than avoiding, the very source of the gap—the place of woman within ethical life—this article seeks to bridge this gap by recovering two liberatory strategies that, the authors argue, Hegel inscribes into his account of the family. The first liberatory strategy is negative, and concerns woman’s liberation from fixed identity. The second, positive, strategy concerns the overlooked diversity of ways that familial freedom, as rightfully ethical love, can be concretely lived. The authors argue that bridging this gap speaks to contemporary perplexities concerning the elements, satisfactions, legal-institutional boundaries, and reasons we attribute to the modern family as well as rethinks the meaning of identity and diversity within the family in ways that provide a compelling alternative to more outwardly flexible liberal theories of the family.

Abstract: Despite a profound concern for the epistemological, ontological and ethical conditions for being-at-home-in-the-world, G.W.F. Hegel published very little on a particularly serious threat to being-at-home: mental illness and disorder. The chief exception is found in Hegel's Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830). In this work, Hegel briefly provides an ontology of madness (Verrücktheit), wherein madness consists in the inward collapsing of subjectivity and objectivity into the individual's unconscious and primordial feeling soul. While there has been an increasing number of studies on Hegel's conception of madness, I propose that there is another overlooked way to understand madness in Hegel's system: as social pathology. I argue in this article that Hegel offers a compelling social account of madness in the Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), which arises at the elevated, self-reflective and community level of spirit. This sociality of madness, as I call it, occurs when spirit is unable to reconcile two contradictory yet equally essential aspects of its reality, resulting in spirit's structural homelessness. I argue that by examining this overlooked sociality of madness, we may read Hegel's political-philosophical project in a new light: on the one hand, the ethical life (Sittlichkeit) presented in the Philosophy of Right (1821) becomes understood as a political therapeutic. On the other hand, if the ethical life fails to live up to the demand of being an adequate spiritual therapeutic, then the traditional reading of the Philosophy of Right as a reconciliatory hermeneutic becomes problematized, opening up new avenues for the proliferation of social pathology.